- Home

- Will McIntosh

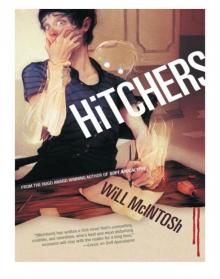

Hitchers Page 6

Hitchers Read online

Page 6

Maybe my new shrink would help me figure it out.

If anyone had told me my first visit to a psychiatrist would not center around living through an attack that killed half a million people, or the drowning of my twin sister, or the horrible death of my wife, but my relationship with my mean old shithound of a grandfather, I would not have believed it.

We’d spent half an hour going over my outbursts, massaging them for significance. The first thing she’d noticed was that they had nothing to do with the anthrax attack, and that surprised her. Evidently the stuff coming up from deep inside me should be rabid, twitching terror.

She noticed that a lot of them referred to Grandpa, and asked if I had unfinished business with him. I admitted that as Toy Shop got more popular, I felt like more of a fraud for continuing it against his wishes. I told her about the argument we’d had the last time I saw him, how I’d gone to his studio clutching my demo strips, full of hope, how we’d gone back and forth, both of us getting angrier until he finally told me I was a hack.

“Just because you have someone in your family who’s an artist doesn’t make you one,” he’d said.

I’d told him he was no artist, that he trotted out the same characters in the same poses year after year, telling the same corny jokes, that the only people still reading were old ladies. That’s when he kicked me out.

I turned from the window and pondered the two original strips hanging framed over my drawing table, side-by-side: Grandpa’s last, my first.

You can tell a lot about a cartoonist from the final strip (assuming he or she knew it was the final strip). Charles Schulz’s last strip was mostly text—a polite, sincere, slightly distant note saying he wasn’t able to continue the strip, and that he appreciated his fans’ support over the years. I’d been disappointed—I wanted the characters to say goodbye, not Schulz. But it was fitting in a way, because Schulz was a stoic Midwesterner. An emotional goodbye would have been out of character.

Bill Watterson had done a better job saying goodbye to Calvin and Hobbes. Our heroes are in the woods, walking through freshly fallen snow. They climb onto their toboggan, and in the final panel Calvin says, “It’s a magical world, Hobbes, ’ol buddy... Let’s go exploring!” It says goodbye, but it’s also hopeful. And why not? Watterson wasn’t dying, only moving on.

In my grandfather’s final strip, Tina drops a Christmas ornament while unpacking a box of them. Little Joe, who’s in another aisle, calls out, “Holy smokes, Tina, more ornaments??” To which Tina replies, “No, Little Joe, less ornaments.” He’d left a Post-it attached to the strip: “A good one. Save for last.”

Grandpa’s last and my first. The end, the new beginning.

Only it hadn’t been a new beginning; not at first. Same old strip, same Little Joe and Tina. I’d even retained Little Joe’s two outdated signature exclamations—Holy smokes! and zounds!”

Readers don’t like it when you screw with their strips, Steve, my agent, had said. Comic strips are supposed to be comforting—people read them over coffee when they’re still waking up and aren’t ready for surprises.

I wandered into the kitchen, pulled open the freezer to find something for dinner. I tended to avoid TV dinners and chicken pot pies, not because I didn’t like them, but because eating them lent a certain pathetic quality to the act of eating alone. Somehow a frozen burrito or an Amy’s rice bowl didn’t carry the same stigma; they were lazy meals, but not cliches that made me feel pitiful.

Yet I was holding a chicken pot pie, considering whether to swallow my pride in exchange for something warmer and homier than a Kashi sweet and sour chicken entree, when my phone rang.

“Yeah, Finn Darby?” the person on the other end said before I had a chance to speak. The voice had a British accent, cockney-thick to the point of parody.

“Yes?” I said tentatively. It didn’t sound like a telemarketer.

“Mick Mercury calling.”

I laughed while I set the pot pie back in the freezer and closed the door. I tried running down a mental file of people who might really be on the other end of the line, but came up blank. “Mick Mercury. The rock star Mick Mercury?” Steve was my only guess. The accent was impressive.

“Yeah, that’s right. I got your number from your agent. Hope that’s okay.”

I hesitated. I didn’t want to fall for a prank; on the other hand the voice sounded an awful lot like Mick Mercury’s.

“Of course.” I sat at my kitchen table, where I’d already poured a glass of orange juice to go with whatever frozen entree I ultimately selected.

“Great, great,” he said.

I had no idea what to say, or who I was talking to, so I just sat there turning my glass.

“I’m a great fan of your work,” Mick Mercury said. “It’s art, what you’re doing with that little strip.”

“Well, thanks,” I laughed.

Every time he spoke my suspicion grew that it really was Mercury. He wasn’t super-famous any more, so it wasn’t totally inconceivable. For a while in the 1980s, though, he’d been bigger than Springsteen, bigger than U2.

I wondered if he was waiting for me to say something. What could I say? I’m a fan? Truth was, I was a fan. I had all five of his CDs. Actually, he’d probably recorded more than five, but I had the important ones he cut back in the early ’80s when he was the Bob Marley of punk/new wave.

“That’s not really why I’m calling, though,” Mercury said.

“Sure,” I said, trying to anticipate the real reason. Did he want to do a song that involved Toy Shop? I didn’t think he needed my permission for something like that.

“I’m going to tell you something that’s for your ears only, yeah?” Mick asked.

“Of course.” We celebrities have a code of silence, after all. It really was him. This was beyond surreal.

“Brilliant,” Mick said. “So I’ll just say it.” He took a big breath. “I had a heart attack on the night of the anthrax attack. I was at my flat in Buckhead.”

“Oh, wow.” I was amazed that he’d managed to keep something like that secret. “Very sorry to hear it,” I added.

“I was dead for five, six minutes before a doctor who lives down the hall resuscitated me. Just luck I had a doctor for a neighbor.”

“Jeez.”

“Yeah, well, I lived too well in my younger years. My middle-aged years as well. Right into my late middle-years, actually.”

I chuckled. Mick Mercury’s struggles with alcohol and pills were well known to anyone who glanced at the tabloid headlines while waiting in line at the grocery store.

“They’re my friends, too.” Mick croaked.

I yelped in surprise. There was no mistaking that zombie baritone.

“‘Scuse me,” Mick said, as if he’d just burped. He cleared his throat. “Maybe you can guess why I’m calling? Can’t help saying things I didn’t say. If you know what I mean.”

My hand was shaking so badly I could barely grip the phone. It wasn’t only me. My mind raced with the implications. It had to be a side effect of exposure to anthrax. The hell with the doctor’s opinion, and the shrink’s. They were wrong.

“How did you know to call me?” I asked, trying not to sound paranoid.

“Funny thing: we’ve got the same neurologist. He didn’t tell me, though—it was one of the birds that works in the office.”

I could picture one of the cute young receptionists telling the rock star about me, basking in his gratitude, leaning into the pat on the shoulder he gave her.

“Is yours the same?” Mick asked. “I mean, does your voice sound like mine?”

“Yes,” I said. “I nearly dropped the phone when I heard it.”

When Mercury finally spoke, he sounded close to tears. “Don’t take this the wrong way, but I’m so fucking relieved to hear that.”

“No, believe me, I understand.” It occurred to me that I should invite him over, to share what we knew. Why not? I opened my mouth feeling like I had when I f

irst asked Lorena on a date. “Maybe we should get together, exchange notes? It might help us figure out what’s going on.”

“Yeah, brilliant. That’s just what I was thinking. You free right now?”

“Sure,” I said, flushing with pleasure.

Mick laughed. “Hell, what else would you be doing, yeah? You can’t go to a bloody movie without scaring the popcorn out of the rest of the audience. You know anywhere we could get good pancakes and a scotch?”

“I have three good days, then the chemo takes three, ” I croaked.

CHAPTER 11

My palms were sweating. I wiped them on my napkin, adjusted my mask so the rubber band wasn’t rubbing against my ear.

I’d arrived at the Blue Boy Diner fifteen minutes early, got us a window booth with a view of the muddy brown Ogeechee. The Blue Boy was an old aluminum diner that smelled of home fries and cinnamon buns. Usually there was a half-hour wait for a seat; today there were less than a dozen people in the place.

I hadn’t been back there since the day Lorena died. I’d expected memories to come flooding in as soon as I drove up, but my mind was preoccupied with the voices-both mine and Mick Mercury’s.

Mick Mercury. As I waited I tried to estimate how old he would be. In his heyday he’d probably been in his early 30s. That was twenty-eight years ago, so he’d be in his late fifties.

I wasn’t sure what to expect. Mercury had been arrested a few times in the past decade, most famously for heaving a car battery through a bar window, nearly braining a man who had taunted him for the way he was dressed. From what I remembered he wasn’t superrich any more. Bad investments, divorce, greedy managers, and a lengthy legal dispute with the guy who co-wrote a lot of his songs had all taken bites out of his net worth.

A man appeared at the entrance. My heart began to thump, then I saw he was with a woman, and he was short and bald, and I relaxed. The hostess led them to an open table. It occurred to me that, even when Atlantans began returning to their normal routines, there would be far fewer filling restaurants and subway cars. Close to fifteen percent fewer, at least until others started moving to Atlanta to take advantage of all the job openings and drastically reduced rents. Assuming people wanted to live in a place that had been the target of the worst terrorist attack in history. My guess was that wouldn’t stop people. The city would eventually rise again.

“Can I get you something to drink?” The waitress’s voice pulled me out of my thoughts. I looked up and was immediately drawn to the tattoos on her forearms: assault rifles morphing into flowers. I laughed, shook my head in disbelief.

The waitress tilted her head, smiled beneath her mask. “What’s funny?” She was an attractive woman, with warm, bright eyes and a relaxed self-assurance that was slightly disconcerting. She was in her late twenties, small and thin, black hair pulled into stubby pigtails with orange rubber bands.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “You wouldn’t remember me, but you’d remember my wife.”

She folded her arms, masking the flower on her right forearm, leaving only the rifle. “Why’s that?”

“You got into an argument with her once.”

The waitress shook her head. “When was this?”

“Two years ago? Springtime. My wife was lactose intolerant,” I explained. “She told you to keep all the dairy products off her plate. You forgot to hold the butter-there was a big scoop on the pancakes. She asked you to get her new ones, but you didn’t see why she couldn’t just scrape the butter off.”

The waitress was still shaking her head, no hint of recognition.

“You got huffy. That’s when she got in your face, told you she didn’t like your tone of voice. She was tall? Latino?”

Her eyes got wide. She pointed at me. “Perfect hair? Expensive hiking boots?”

I pointed back. “That’s her.”

The waitress let her head loll back until she was looking at the ceiling. “God, that was a terrible morning. My daughter had been throwing up all night, then I couldn’t find anyone to watch her and I was late getting to work.” She pressed her hand to the side of her face. “By the time I got to the butter thing I had nothing left. I just couldn’t conjure up the cheery singsong waitress voice.”

“No,” I laughed, “you definitely couldn’t.” I didn’t know what it was about this woman. She had an energy that made me wish I could go on talking to her.

She glanced toward the door, widening her eyes theatrically. “She’s not meeting you here, is she? Should I hide?”

I felt a pang. “No, no.” I shrugged.

“Well, please tell her I’m sorry.”

I shrugged. “She died, actually.” I had never come up with an easy way to say it. And for some reason it seemed important to add, “Believe it or not, it was the same day as that argument.”

The waitress pressed a hand to her chest. “Oh, God, I’m so sorry.” I felt it welling up, but could do nothing to stop it. “I’m telling ya, she’s a little tramp,” I croaked.

The waitress gasped, her hand flying to her mouth.

“I’m sorry,” I said, covering my own masked mouth. “I didn’t mean to say that. My doctor says I’ve got some sort of neurological disorder. He thinks it’s temporary. It’s not contagious.”

“Oh.” She reached as if to touch my hand, but didn’t quite. “Oh. That’s terrible. I’m so sorry. About your wife, and—” she paused, reaching for a word, “your problem.” I could see from her face that she was more scared than sorry. She recovered her composure, cleared her throat. “So can I get you something to drink?”

Before I could answer a buzz of excitement rose through the diner. I leaned around the waitress to see the door.

There he was. Unmistakable, speaking into the other waitress’s ear, a hand on her shoulder. He still had the spiky blonde hair, and his outfit, though not particularly loud or flashy, announced that he was someone of note: black-rimmed hipster glasses, expensive leather jacket, jeans. He wasn’t wearing a mask—the only person in the diner.

I waved. He spotted me, gave me a two-fingered salute, sauntered over wearing a big smile, his hand outstretched. I met him partway and we shook, then he clapped my shoulders as if making sure I was real.

A young woman was hovering behind him, clutching a pen. I motioned to Mick. He turned, exchanged a few pleasantries with the woman as he signed her napkin.

A few other admirers left their booths to meet him. Mercury gave his attention to each of them in turn, listened to their brief testimonials—how they’d seen him at his first Atlanta concert, what this or that song meant to them. He seemed to enjoy himself.

When an elderly woman came forward, her hand outstretched, Mick blurted, “Mom, not in the middle of my show.”

The woman let out a startled “Eep”; others gasped in surprise.

“Sorry,” Mick said, holding his palm over his mouth. “Been working on a new vocal style. Thinking I might try crossing over into some of that Goth vampire music.” He grinned brightly, eliciting a few nervous chuckles. “Finn and me are going to have some breakfast now, so if you don’t mind...” He gave everyone a gentle “shove off” gesture.

When everyone was back at their tables, Mick and I settled in.

“So. What the fuck is wrong with us?” Mick murmured.

I took a quick sip of water—my mouth was dry. It was jarring, to realize I was sitting with a rock star. I found it impossible to look across the table at Mick Mercury and see nothing but another guy. It was Mick freaking Mercury.

“Seems to me it’s got to be connected to the anthrax,” I said.

Mick pointed at me, nodding emphatically. “That’s what I said, but the doctor said it ain’t possible.”

The waitress came over. I stared at the table, still embarrassed by my outburst, and it seemed as if she was standing a lot further from the table than she’d been before. She was wearing gold sneaker-shoes with Cleopatra’s face on them.

She gave Mick a level look. “Just so

we’re clear, I’m not going to ask for your autograph or anything juvenile like that.” She shrugged. “But if you happened to sign that place mat for some reason, that would be okay.”

Mick grinned. “I’ve done stranger things.”

“Yes you have,” the waitress shot back, prompting Mick to cackle madly.

True to his word, Mick ordered a scotch with his bacon and pancakes.

When the waitress had gone, I said, “The doctor told me the same thing. But it’s the only thing that connects our cases. That and the fact that we both died for a few minutes.”

We compared notes. The things we were blurting were similar in some ways, not in others. I recognized a lot of what I said—it had to do with the strip, people and places I knew, and especially my grandfather. Mick recognized some of what he said—about his music, the lawsuit he’d fought with his collaborator, and so on. Other things weren’t at all familiar, like the beauty he’d just uttered.

“Sometimes it’s like I got a bleeding anorak in my throat. Programs on the telly, comic books. I go on and on about the most trivial dross.”

It definitely didn’t fit with my psychiatrist Corinne’s theory that my blurting was the result of unresolved issues with my grandfather. If that was it, why would Mick Mercury have the same problem?

“Let me ask you something,” Mick said, leaning forward, his elbows on the table. “You much for getting trolleyed?”

I shook my head, totally lost.

“You know, do you like to get pissed?”

It took me a minute, then I remembered that pissed was British for drunk. “Oh sure, I like a few drinks now and then.”

Mick nodded, looked around, as if afraid some of the patrons might be undercover paparazzi. “But when you’re done having those few drinks, do you have a few more?”

The Heist

The Heist Faller

Faller City Living

City Living The Perimeter

The Perimeter Watchdog

Watchdog Defenders

Defenders Soft Apocalypse

Soft Apocalypse Futures Near and Far

Futures Near and Far Unbreakable

Unbreakable The Future Will Be BS Free

The Future Will Be BS Free Hitchers

Hitchers Burning Midnight

Burning Midnight Watching Over Us

Watching Over Us